Obesity and the Invisible Triggers in Our Environment

Over the last 150 years, obesity has steadily increased in the United States — with a sharp rise in recent decades. Currently, more than 35% of American adults and nearly 17% of children and adolescents (aged 2 to 19) are considered obese. But the problem isn’t exclusive to the U.S.: obesity is on the rise worldwide, even in developing countries.

This growing trend can also be observed among animals — including pets, lab animals, and urban rodents — all of which have shown an increase in average body weight. And here’s the curious part: this weight gain isn’t always explained by diet or physical inactivity. As Robert H. Lustig, a clinical pediatrics professor at the University of California, San Francisco, states: “Even those at the lower end of the BMI curve are gaining weight. Whatever is happening is happening to everyone, suggesting an environmental trigger.”

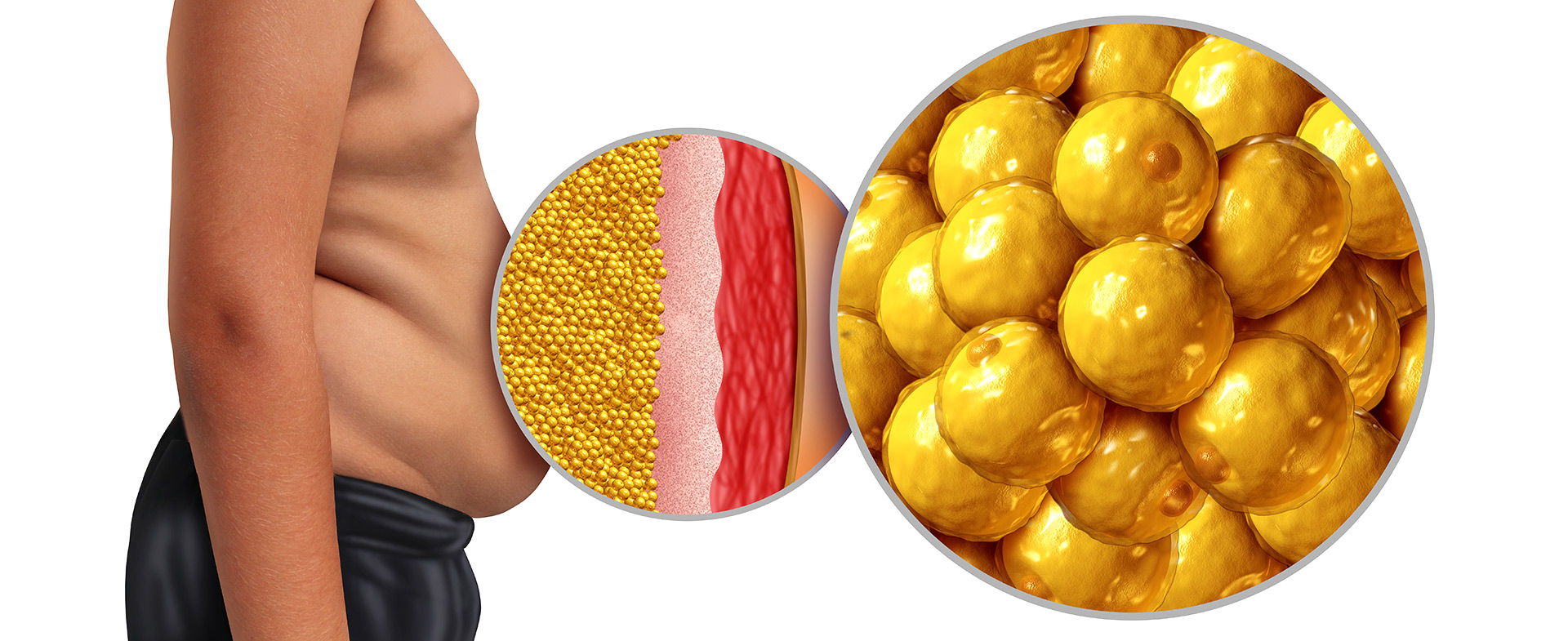

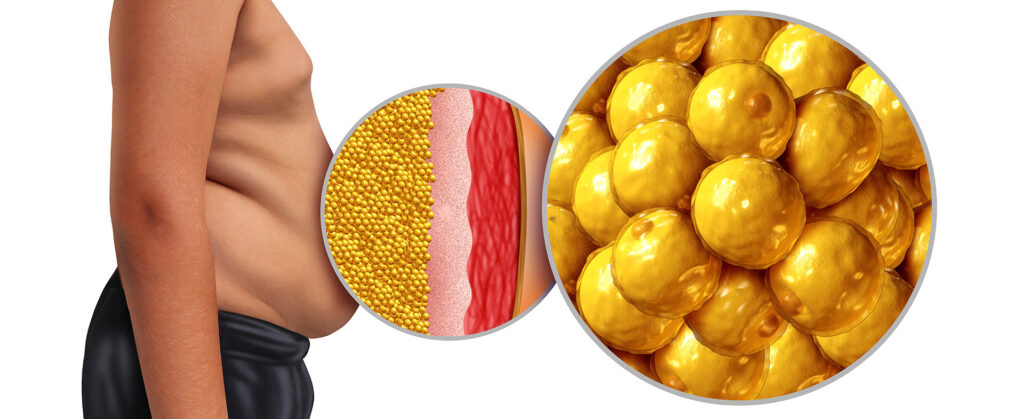

For a long time, the medical community pointed to poor diet and lack of exercise as the main causes of obesity. But research increasingly supports another factor: obesogens — chemical compounds in food, pharmaceuticals, and the environment that may disrupt metabolism and predispose people to gain weight.

What Are Obesogens?

The concept of obesogens gained ground after Paula Baillie-Hamilton published an article in 2002 proposing that low-dose chemical exposures could be linked to weight gain. Since then, numerous studies — on both animals and humans — have investigated how these substances can interfere with the body’s regulation of fat.

Obesogens may act in various ways: some increase the number or size of fat cells, while others alter hormones related to appetite and energy use. Some effects even begin before birth — during fetal development — and persist throughout life.

One of the scientists who advanced this theory is Bruce Blumberg of the University of California, Irvine. In 2006, he coined the term “obesogen” after discovering that tributyltin (TBT), a chemical compound, caused lab mice to gain weight. Even when these mice were fed a normal diet, they still gained more fat, indicating a metabolic shift caused by chemical exposure.

How Do These Chemicals Work?

Many obesogens are endocrine disruptors — substances that interfere with the body’s hormonal system. For example, TBT activates PPARγ, a nuclear receptor that controls the formation of fat cells. Once activated, it encourages precursor cells to become fat-storing cells. This effect can be permanent if exposure happens in utero.

Other substances that may act as obesogens include:

- BPA (found in plastics and food can linings)

- Phthalates (used in personal care products and PVC plastics)

- Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (used in non-stick cookware and stain-resistant fabrics)

- Pesticides like atrazine and DDE

- Certain medications, such as rosiglitazone (Avandia®)

- Food additives like monosodium glutamate (MSG)

Some of these substances have even been found in household dust, furniture, clothing, and cosmetics.

Obesogens and Future Generations

One of the most concerning aspects of obesogens is that their effects can be passed on to future generations. This happens not through changes in DNA sequences, but through epigenetic alterations — changes in how genes are expressed.

For example, research has shown that mice exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES), a synthetic estrogen once prescribed to pregnant women, experienced altered fat distribution and long-term weight gain. Similarly, exposure to BPA and PFOA in the womb has been linked to obesity in offspring — even if the chemical is no longer present after birth.

Prevention and Awareness

So, is obesity inevitable for those exposed to obesogens early in life? Not necessarily. While these exposures may shift the body’s tendency toward fat accumulation, lifestyle choices still play a role. A healthy diet and physical activity remain crucial, especially for individuals who may be more vulnerable due to their metabolic programming.

Reducing exposure to environmental chemicals is also essential. Choosing safer household products, avoiding unnecessary plastic use, and being mindful of food packaging can make a difference — especially during pregnancy and early childhood, when susceptibility is higher.

In the end, fighting obesity may require more than just individual willpower. It also means understanding the hidden influences around us — and pushing for policies that protect our environment and our health.

text-based -

https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/ehp.120-a62